The UK is styling itself as a global leader in space sustainability with the UK Space Agency (UKSA) underpinning a range of new initiatives. Heading up this work, a varied role ranging from developing sustainability standards to leading a national debris removal mission, is Ray Fielding. ROOM Editor-in-Chief, Clive Simpson caught up with him after his participation in the Secure World Foundation’s ‘5th Summit for Space Sustainability’ held in New York this summer.

Space sustainability is a hot topic today - could you explain to readers how important it is for the future of both space exploration and commercialisation?

We need to prioritise space sustainability to make sure that while we are using the environment of space to meet the current and future needs of society, we are also preserving that environment for future generations.

Although we may think of space as being vast, the bits that we use, particularly the areas around Earth, are actually quite constrained and fragile. Low Earth orbits (LEO), where we find Earth observation satellites and the new broadband range of satellites, is quite a small shell of geo-spatial area and the same is true of medium orbits, where GPS satellites operate, and higher geosynchronous orbits.

Our dependence on the data we get back from satellites and the capabilities which satellites and space operations give us is only going to grow with advances in areas like in-orbit manufacturing and in-orbit operations, to provide things like space-based solar power or increased access to space for humans. The last thing we want is to reach a point where operating in space becomes too hazardous or even impossible due to the high volume of space debris

From a UK Space Agency perspective how would you define sustainability and what sort of role is the UKSA taking on a global scale?

We need to prioritise space sustainability to make sure that while we are using the environment of space to meet the current and future needs of society, we are also preserving it for future generations

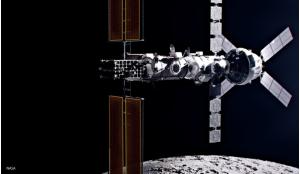

That’s a timely question. Currently we are conducting an exercise with experts across different domains to come up with a useful and robust definition of ‘sustainability’. Traditionally we’ve looked at the various Earth orbits but we’re now actively considering whether we want to extend what we mean by space sustainability to include things like lunar orbit, or beyond; to ensure we embed sustainability principles and operation into deep space missions too.

There are a number of reasons why we want to take a global lead in this. We are now the world’s second largest operator of satellites and we want to be an open and inviting environment for space operators to work from, and to be licensed and regulated from. We want to grow the UK space sector and to pull in investments, and one of the ways we can do that is to become an attractive place, a principled place that shows people that sustainability is important to the UK. We’re going to take a lead in this and put our money where our mouth is by developing sustainable operating practices.

We are looking into a range of supporting study work and working through organisations such as the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) where all the different space agencies come together to look at removing debris. If you wanted to, you could go through the whole lifecycle - supply chains, rocket fuel, space ports, some of which would encompass all sorts of terrestrial sustainability legislation as well as space sustainability. There are natural relationships to be had with different UK organisations and parts of the government, as well as different organisations across the world. We’re actively working to define what those might be and to identify the bits the UK Space Agency wants to lead on.

Does space sustainability include Earth’s atmosphere? Thinking about the potential for damage by chemical compounds that could be added by objects burning up in the atmosphere, is that a problem to be looked at?

On the question of upper atmosphere aerosols and the possible effect of deorbiting what could be many objects into the upper atmosphere for burning up, we are looking to work with others to study that cause and effect on a large scale. We don’t know yet. Currently very few objects come down, and those that do are thought to burn up to such a degree that they are almost down to individual atoms, so it’s not thought to be too much of an issue. But when you consider that the estimated number of satellites could be 50,000 by 2030 and with the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) now requiring satellite operators in low-Earth orbit to dispose of their satellites within five years of completing their missions, shortening the decades-old 25-year guideline for deorbiting satellites post-mission, that’s a lot of objects potentially coming down.

Am I correct in thinking there are four general thematic areas that demonstrate the way sustainability is being tackled: space surveillance and tracking, standards of policy, international collaboration and technology?

Yes, that sums it up well. We need space surveillance and tracking in order to identify areas of concern. Mitigating against the problem requires working with others to develop international standards and regulations.

Actively doing something – going after debris before it becomes a collision hazard or causes greater problems, and planning how to manage future levels of debris, will be made increasingly possible by technology developments and by working with others to make sure that the problem is tackled globally.

All of these areas are interrelated. You can’t have one of them without the others. It’s better to mitigate against the problem in the first place than to clean up after, but the activities need to work in parallel, and we can’t do that unless we work with others, and through others on a global scale.

The UK-sponsored Active Debris Removal (ADR) mission is getting a bit of publicity now. Could you explain why it’s important and what we could expect it to lead to in the longer term?

When you have thousands of satellites operating in the same area, and satellites heading directly towards each other, who decides who manoeuvres?

The ADR mission is important for a couple of reasons. Firstly, we need to do something about space debris and the UK government has liability for UK registered objects. If they become a hazard either by falling to Earth in places you really don’t want them to, or by damaging national or international assets in orbit, there’s a potential liability question, so we don’t want that to happen. But equally, developing ADR technology gives you a whole range of capabilities which are useful to promote the space sector, to grow the industry and grow our presence in space. For instance, having the ability to remotely dock with a satellite or piece of debris that is tumbling, spinning or is otherwise out of control, gives you a range of capabilities which you can use for other things too.

There’s the potential to offer services to constellation operators who may not want their own debris-removing satellites but who have a commercial interest in keeping their constellations functioning safely and bringing in revenue. Not only that, if you have the capability to dock with satellites you can also service or refuel them. If you can remotely operate in space, you can construct things in space, even develop manufacturing stations to cheaply manufacture things that would be more costly or impossible to do on Earth, realising the benefits that microgravity gives you.

Developing new capabilities leads to new markets, to growth, and investment in the sector, which as a space agency is what we’re really trying to foster. I’d like to think we are taking a lead in this area because we’re not just doing it domestically, we’re also investing through the European Space Agency on debris removal mission concepts

At the sustainability-themed conference organised by the Portuguese Space Agency this summer there was much discussion about space law and its role in the context of supporting space sustainability. It’s a complex area fraught with difficulties at an international level – can the UK play a role in securing agreements?

There are a couple of things we are already doing in that area. We are working with the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UN COPUOS) and with international partners and allies to support the principles of the long-term sustainability guidelines from the UN, and we’re also developing sustainability standards for the UK. The latter is an area we’ve just kicked off, which will look at all areas of sustainability, including the lifecycle of space missions, to ensure sustainability is embedded and operated 100 percent through whatever a space operator in the UK wants to do. That will eventually become a British Standard Kitemark, a certification which confirms a product or service’s claim has been independently and repeatedly tested by experts, also potentially an ISO standard, so again, it’s something the UK is taking a lead in.

Although the work that has been commissioned to establish sustainability standards is being funded by the UK Space Agency it’s very much for the good of all, so we have the investment market, the insurance market, and the space actors and space operators involved. We’re trying to achieve a standard which is a balance between operating sustainably and operating commercially. Hopefully, in the next couple of years, we’ll have a set of standards for activities in space, which we’ll be able to give sustainability accreditation for.

Are industry and academia producing their own initiatives on sustainability that either complement or contrast with the UK Space Agency approach?

We’re trying to be as joined up in our approach as possible. George Freeman MP, UK Minister of State for Science, Research and Innovation, has been leading a series of round tables on space sustainability, space standards and space policy, to ensure that everyone has a say. With regard to industry, I work on a regular basis through groups such as UKspace, the official trade association of the UK space industry, to ensure that the investments made in technology are aligned with what the industry needs and tackle the problems that are holding it back. We need to remain cognisant of the twin drivers of commercial sustainability and space sustainability. And certainly, we’re very plugged in to what the academic community is doing, with studies to make sure we commission meaningful work that tackles perceived gaps in space research, in line with what the UK wants to achieve in terms of national space strategy. We will work together as a coherent whole to achieve that strategy.

Is China part of your discussions and international partnerships?

It won’t work if some of us ‘do’ space sustainability while others ‘don’t

We engage with everybody across the world when attending COPUOS sessions, or the Long-term Sustainability Guidelines Working Groups under the auspices of the UN. We speak to China and many other nations on a regular basis because this is a shared global problem. It won’t work if some of us ‘do’ space sustainability while others ‘don’t’. Space doesn’t have borders, objects in space are very mobile and problems which affect us all don’t just stay in one place, so we need to do this collectively on a global basis, so we speak to everyone.

This year we have seen an ever-increasing number of launches each with the potential to increase the proliferation of space debris. Do governments and the space industry have a ‘deadline’ to get on top of this and, if we don’t act quickly enough, do you see a time when it may be too late?

That’s a very interesting question. We are working to understand if there is a need for a target and timeline for space, similar to the Paris Accords with its climate change targets. It’s felt that there might be, and we’re working with other governments, space operators and constellation operators to understand their thoughts on the subject. Leading academics have been involved in that work as well.

If a need is identified, I believe that will drive timelines. This is a problem we need to get a grip on in the short term, rather than the long term. We are facing quite an issue with space debris. At present, depending on the references you use, there are between 25,000 and 30,000 large space debris objects. That’s quite significant, considering there are only 8500 (August 2023] operational satellites. It means that non-operational satellites and space junk far outweigh in-orbit operations. And that’s not forgetting that there are between 1,000,000 and 3,000,000 small objects, less than 5 cm in size. This cloud of debris is rapidly going to get out of control unless we get a grip on it.

How we effectively manage space traffic is another issue - when you have thousands of satellites operating in the same area, and satellites heading directly towards each other, who decides who manoeuvres? To move expends fuel, reducing operational life, so there’s a monetary cost to it. I think that probably the only way to manage the process will be automation but for that regulation and agreement needs to happen pretty quickly.

The UK wants to be seen as a responsible and sustainable space operator. We want to be an attractive place for UK companies and others around the world to operate from, so we can attract investment into the country and grow the space sector, and obviously the economy as well. There’s a balance to be had between total non-regulated commercial operation of space and total regulation where it becomes impossible to utilise and benefit from space, and we want to find that balance.

We have the opportunity, like the one we had with our planet’s environment 50 to 60 years ago when we could have taken actions to limit or avoid the levels of climate change we now face on Earth. We need to do everything we can do to avoid the same scenario in Earth orbit. The space environment is fragile, we need to preserve it.

About the interviewee

Ray Fielding, a materials engineer by training, has spent over 20 years delivering and leading cutting edge technology projects in the defence research and space sectors. Previous roles have included programme leader for sustainable operations for the UK MoD and head of the sustainable development International Partnership Programme at UKSA. Ray is now Head of Space Sustainability at UKSA, a varied role ranging from developing sustainability standards to leading a national active debris removal mission.