Are we witnessing the end of international space law as we know it, or are we on the brink of a transformative era? This special report, based on a chapter from a new book published in honour of esteemed international law professor Siegfried Wiessner, gets to the heart of the matter, exploring whether international space law is undergoing drastic change or just simply fading away. Amidst geopolitical turmoil and waning international cooperation, the possibility of a new intergovernmental organisation dedicated to space affairs emerges as a critical consideration. The future of space governance hangs in a delicate balance.

For a prolonged period of human history, small and powerful groups have used laws and regulations to control, govern and enhance the welfare of organised communities in various domains throughout the world. From monarchs to emperors, from authoritarian dictators to modern forms of democratic governance across the world, leaders have aimed to prevent ‘lawlessness’ or ‘rule of the jungle’ situations where survival of the fittest prevails. The domain of outer space is no exception in this regard. The adoption of laws, both national and international, is an effort to achieve welfare for all of humankind in the space domain.

After centuries of relentless exploitation and colonisation and two devastating world wars, the international community came together to create institutions and enact laws and regulations at the international level that were universally recognised and adhered to. However, with the passage of time, the preference of the international community (mainly the major spacefaring countries) has seemingly changed. Newer forms of international regulations are being explored and devised to match the rapid pace in advancements in technological sectors, and extra-legal factors are having a marked influence on the adoption and application of international space law.

Human beings are now increasingly capable of expressing and conveying ideas and notions in a global and inter-connected world made possible, in part, by space-based technologies, aided and assisted by technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), social media, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the cyber domain. Through the proliferation of and increased access to new technologies, traditionally and historically imparted laws and regulations, particularly international law and international relations, are being torn apart bit by bit.

The Lisbon Declaration on Outer Space in the context of the Management and Sustainability of Outer Space Activities was ratified in May 2024.

The Lisbon Declaration on Outer Space in the context of the Management and Sustainability of Outer Space Activities was ratified in May 2024.

The end of law results in the law of the jungle, a state of affairs in which some gain absolute freedom while the freedom of others is significantly restrained, if not totally lost. In today’s world, the complete end of law may not be conceivable. However, limiting the scope of law, its routine disregard, ineffective implementation, intentional weakening or clear violations of international law is cause for alarm.

Trend towards exclusivity

The end of law results in the law of the jungle, a state of affairs in which some gain absolute freedom while the freedom of others is significantly restrained

Although a number of legal principles have been adopted to safeguard and enhance inclusive interests of all States in the domain of human activities in outer space, the actual conduct of some major spacefaring nations has started a contradictory trend. Within a few years of the negotiation of the Moon Agreement in 1979, developments in the space sector indicated a move towards the exclusive interests of some States. Space activity and conduct quickly became a hallmark of geopolitical hegemony, a means for asserting economic and strategic superiority and dominance, and hinted at the beginning of unilateralism.

Currently, the increasing participation, presence and ever-expanding assertiveness of non-governmental entities or private companies have made exploration and use of the space domain more complex and difficult. Moreover, the presence and increased reliance on the conduct of private space actors is impacting the conduct of their respective States in matters related to space technologies and in the formulation and application of international space law.

There has been a failure to evolve the framework of international space law, or more broadly, a failure to holistically expand and strengthen the global space governance system to ensure it is better suited for modern times. Since 1979, no space law treaty has been adopted by the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UN COPUOS), which implies that its role as the main international forum for the progressive development of international space law is gradually being undermined. Outside the UN framework, no progress has been made either. As a consequence, the expansion of international space law is virtually at a standstill.

MASTER the European Space Agency’s debris and meteoroid risk assessment tool covers debris and micrometeoroids between 0.001 mm and 100 m. An exponential increase in the privatisation and commercialisation of space activities, as well as space militarisation and weaponisation has resulted in greater congestion and competition in outer space and has been responsible for the creation of an enormous amount of space debris.

MASTER the European Space Agency’s debris and meteoroid risk assessment tool covers debris and micrometeoroids between 0.001 mm and 100 m. An exponential increase in the privatisation and commercialisation of space activities, as well as space militarisation and weaponisation has resulted in greater congestion and competition in outer space and has been responsible for the creation of an enormous amount of space debris.

In addition, some States are refusing to accept their legal status under international space law as a ‘launching state’, which is contrary to a well-established principle of ‘once a launching state always a launching state’. Such rejection effectively shakes the foundations of international space law which holds the launching state liable for any damage caused by space objects belonging to its public agencies and private entities. Indeed, several Launching States have not been fulfilling their obligation to register with the UN Secretary-General their space objects, including those that are being used in military space activities, that have been launched into Earth orbit or beyond.

There has also been neglect on the part of major spacefaring States to respect the principles contained in Article IX of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. This provision provides the basis to ensure that the space and terrestrial environment is protected from harmful contamination, and obliges States to have due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States when conducting space activities. In addition, as missions to the Moon and Mars for exploitation of natural space resources take place, the possibility of contamination of these bodies may be expected.

Meanwhile, there has been a recent unilateral move to formally and expressly negate the long-standing consensus that outer space is a ‘global commons’, which in turn hints at the dismantling of the foundations on which international space law has been envisioned, built, promulgated and advanced. Most importantly, recent years have witnessed an exponential increase in the privatisation and commercialisation of space activities as well as in space militarisation and weaponisation. Such trends have resulted in greater congestion and competition in outer space and have been responsible for the creation of an enormous amount of pollution in the form of space debris.

These are significant developments in the space domain, and the integrity and sustainability of the global space governance system demands that the rule of law over these matters is maintained, expanded and strengthened. So far, the international community remains unable to effectively regulate such developments and activities.

There has been a failure to evolve the framework of international space law

Finally, there is a lack of effective and formal mechanisms to discuss disagreements and settle disputes. In general, the major spacefaring States have shown an aversion towards setting up and creating a functional international organisation to regularly deal with issues related to international space law and regulations.

All of the above trends seem to be contrary, and pose a threat, to some of the most fundamental principles of international space law that are contained in the five UN space law treaties. These trends indicate, at least in part, the gradual and ongoing move by some major spacefaring States as well as their private companies and actors towards undermining the role and importance of international space law for protecting inclusive global interests of all humankind. This is being done to favour enhancement and protection of their [a State’s] individual exclusive interests.

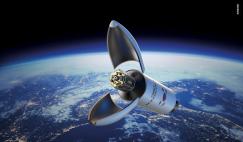

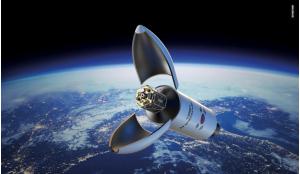

A futuristic anti-satellite weapon capable of destroying satellites using its ‘circular saw’ extensions.

A futuristic anti-satellite weapon capable of destroying satellites using its ‘circular saw’ extensions.

Decline in cooperation

Perhaps the most immediate, pertinent and prevalent factor in international relations is an increasing mistrust among States, a rise in aggressive nationalism and a decline in international cooperation and multilateralism. In addition, there is an utter failure on the part of world governments to envisage and deliver a world that lives and thrives within the carrying capacity of our planet Earth.

Every year since the adoption of the UN 2015–2030 Agenda goals, the UN has annually released Sustainable Development Goals Reports (SDGs). The 2022 version of the report, however, paints a rather worrying picture by observing that “[a]s the world faces cascading and interlinked global crises and conflicts, the aspirations set out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development are in jeopardy.”

A few years marked by a pandemic, climate change events and a global recession resulted in the growth of aggressive nationalism that has influenced the approach and action of States. Consequently, States are moving away from an all-inclusive approach (i.e., leaving no one behind) to preserving and protecting their own national interests. Instead of collective long-term survival goals, dealing with comparatively short-term crises appears to be the priority of the day.

Towards achievement of the UN SDGs, the space sector has the potential to contribute to almost all of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of humanity and, for this purpose, the UN General Assembly adopted the “Space 2030 Agenda: space as a driver of sustainable development” resolution. A few States have started making noteworthy progress in this area. Today, more than 70 space agencies exist in the world, more than 15 States and their private companies possess the ability to launch space objects, and seven states have the capability to send a probe to extra-terrestrial locations such as the Moon, Mars or deep space.

Moreover, in the NewSpace 4.0 era, activities of private enterprises or non-governmental entities often exceed the activities of most States. Since the actions of these enterprises and entities are essentially and exclusively directed at profit-making, space activities are shifting away from international cooperation and from protection of the core principles of international space law which focus on inclusive benefits and interests of all States.

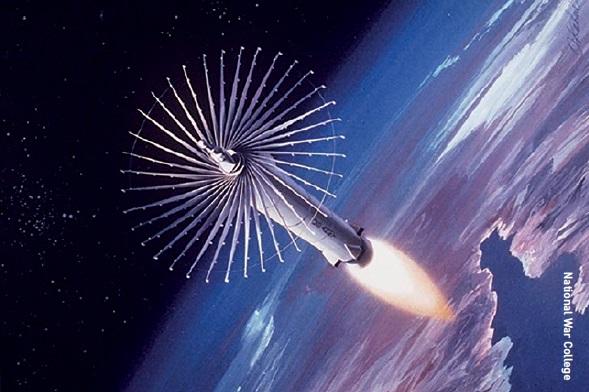

Other factors include the inability of UN COPUOS to make States commit to binding legal agreements, even in matters of urgent and pressing concern to the international community, such as the issue of ever-increasing space debris, and the unilaterally declared intentions of spacefaring States to extract and exploit space natural resources for exclusive national benefits. The long-term sustainability of outer space has further been threatened by States conducting anti-satellite tests that result in the destruction of their own satellites in orbit, and other experiments and manoeuvres that heighten international mistrust and tensions.

Failure to review

The long-term sustainability of outer space has further been threatened by States conducting anti-satellite tests that result in the destruction of their own satellites in orbitA

All these observations are not per se a critique of existing international space law. It is the failure of the international community to review, update and expand this legal regime that has led to a situation that such an important and forward-looking treaty as the Outer Space Treaty is facing challenges to its foundational principles. Given the general despair with regard to the strength and nature of the laws governing outer space and outer space activities, the possibility of major space power(s) withdrawing from this principal treaty (i.e., the five UN Space treaties) is not unthinkable. The global space governance regime is at a crucial inflexion point.

The deteriorating state of general international relations is a key contributor to the current state of affairs. The lack of flexibility shown by Russia and China on one side, and the USA and some of the European powers on the other, has made it impossible for the negotiation, let alone adoption, of a subsequent international treaty on the regulation of outer space.

Persistent geopolitical differences between Russia and the US, and more recently with People’s Republic of China, are major barriers to cooperation in controlling placement of weapons in outer space.

For instance, geopolitical, economic, legal and other related factors and disagreements led to the rejection of the Sino-Russian draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects by the United States and other allied States. In the meantime, the intentional destruction of a State’s own satellite(s) in space has emerged as a means of showcasing military space power and capabilities. All of these trends jeopardise the long-term sustainability of outer space activities and the freedom of exploration and use of outer space by all States.

In relation to activities in the space domain, the hegemonial conduct of certain States has sometimes seeped deep into the attitude of their private corporations. For instance, one large private space corporation has unilaterally and quite explicitly expressed its views that international law is not applicable to a specific space activity or on a celestial body. While such expressions might not have mattered in other areas of international regulation, it is a matter of concern when that particular entity owns and operates around half of all active satellites currently in Earth orbits.

Intuitive Machines Odysseus lander touched down in the Moon s south polar region on 22 February 2024, and has since transmitted valuable scientific data back to Earth. The increasing participation, presence and ever-expanding assertiveness of non-governmental entities or private companies have made exploration and use of the space domain more complex.

Intuitive Machines Odysseus lander touched down in the Moon s south polar region on 22 February 2024, and has since transmitted valuable scientific data back to Earth. The increasing participation, presence and ever-expanding assertiveness of non-governmental entities or private companies have made exploration and use of the space domain more complex.

Debris from megaconstellations

The launch, operation and proposed launches by private companies of megaconstellation(s) comprising thousands of satellites are expected to result in the creation of extensive space debris and the occupation of a fairly large number of radio frequency bands, which are a limited international natural space resource. Such control over radio frequencies is being increasingly seen as attempts at establishing a monopoly in outer space to the exclusion of new entrants in the outer space activities’ domain. Moreover, such private space corporations have been able to carry on their operations with little or no regard for the appropriate protection of dark and quiet skies, as well, and the emerging environmental impact their activities may have on various associated stakeholders.

Additionally, as a result of privatisation of space activities, there has been a blurring of the distinction between public (governmental) and private sector involvement in foreign wars and conflicts. The governmental agencies of major space powers are increasingly relying on the commercial launchers, satellites and services of the private sector for military purposes.

The increasing participation, presence and ever-expanding assertiveness of non-governmental entities or private companies have made exploration and use of the space domain more complex and difficult

The International Committee of the Red Cross has warned that “the weaponisation of outer space would increase the likelihood of hostilities in outer space” and the “human cost of using weapons in outer space that could disrupt, damage, destroy or disable civilian or dual-use space objects is likely to be significant.” Thus, in specific situations and for the use of certain kind of military tactics and manoeuvres in space, certain States can be considered to be in violation of their fundamental obligations under the Outer Space Treaty for carrying out all their space activities, including military space activities “in the interest of maintaining international peace and security and promoting international co-operation and understanding.” All in all, the unwillingness of the major space powers to take steps to halt or reduce the growth of militarisation and weaponisation of outer space activities has been and continues to be a major factor towards the decline in development of and respect for international space law.

There is overall consensus in the international community that space is a “global commons,” the exploration, use and long-term sustainability of which is a common ground to unite the many differing views of States and bring them into a single and pointed action plan and agenda. There is a critical difference between space as a global commons, and an emerging view that space is no one’s domain, or that space is a war-fighting domain.

It is evident there is a failure to effectively regulate private companies or non-governmental entities. Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty obliges States to authorise and maintain continuing supervision over the activities of their private space actors and operators, and States must ensure that all activities of private enterprises are carried out in compliance with the provisions of the Outer Space Treaty. In addition, the “monopolistic and/or considerably dominant” position of private space corporations may be contrary to the principles contained in Article I of the Outer Space Treaty pertaining to the exploration of outer space for the benefit and in the interests of all mankind, the freedom of exploration and use of outer space without discrimination of any kind and on a basis of equality.

SpaceX Starlink satellites before deployment. Starlink is the world’s first and largest satellite constellation using a low Earth orbit to deliver broadband internet. SpaceX owns and operates around half of all active satellites currently in Earth orbits.

SpaceX Starlink satellites before deployment. Starlink is the world’s first and largest satellite constellation using a low Earth orbit to deliver broadband internet. SpaceX owns and operates around half of all active satellites currently in Earth orbits.

Space pollution

The space environment is vast, but the portion of usable space environment in orbits around the Earth that can sustain commercial space operations is fast diminishing, due to space debris. This problem is further complicated by the launch, or proposed launch, of tens of thousands of satellites in the form of large-scale (mega) satellite constellations in already crowded portions of low Earth orbits.

Despite these urgent and pressing issues, the international community has been unable to agree on binding legal commitments to halt the generation of or to significantly reduce the ever-increasing amount of space debris. This course of action hits at the very foundational principles of international space law, i.e. to explore and use space for the benefit and in the interests of all States and to maintain due regard for the interests of all States. The presence of space debris necessarily also acts as a natural obstacle to the entry of newer States wishing to conduct space activities as it makes it more challenging and expensive for these emerging spacefaring States and their private corporations to launch, conduct and sustain operations in outer space.

Soft law instruments in the form of space debris mitigation guidelines have been incorporated into respective national legislations and other policy documents of some States. However, in the absence of any formal legally binding instrument of international space law on the subject matter, and in the absence of an appropriate mechanism to initiate and engage processes towards the making of such a formal legal instrument, it remains uncertain whether the implementation of some of these guidelines by a few States would be sufficient and effective in controlling the ever-increasing problem of space debris. The fact remains that irrespective of efforts in adopting and implementing the guidelines, the amount of space debris continues to grow.

In September 2011, the US National Research Council warned that space debris had reached a “‘tipping point’, with enough currently in orbit to continually collide and create even more debris, raising the risk of spacecraft failures…”. A decade later, in 2021, the G7 Leaders “pledged to take action to tackle the growing hazard of space debris as our planet’s orbit becomes increasingly crowded.” It remains to be seen if, and when, this pledge will be fulfilled.

Private space corporations have been able to carry on their operations with no or little regard for the appropriate protection of dark and quiet skies

Without more proactive space debris remedial or removal measures, there is very limited, if any, hope for a meaningful solution in the near or medium term to the space debris problem that is caused by the actions of a few spacefaring States, and which is expected to pose constraints on the freedom of use of outer space by all States. If no Active Debris Removal (ADR) efforts are undertaken, it is believed that even if no new space objects are launched, the most used low Earth orbits might not be sustainable in a medium to long-term time framework. There are numerous legal, organisational and strategic challenges to effective ADR operations, but none of them are being seriously addressed at the international level.

Artist’s concept of a commercial ice mining venture on the Moon. The position of private space actors and operators may be contrary to the principles contained in Article I of the Outer Space Treaty regarding the exploration of outer space for the benefit and in the interests of all mankind, the freedom of exploration and use of outer space without discrimination of any kind and on a basis of equality.

Artist’s concept of a commercial ice mining venture on the Moon. The position of private space actors and operators may be contrary to the principles contained in Article I of the Outer Space Treaty regarding the exploration of outer space for the benefit and in the interests of all mankind, the freedom of exploration and use of outer space without discrimination of any kind and on a basis of equality.

Possible solution

Given the fact that humankind is at an inflexion point and undergoing a transitional phase that will make or break the international system pertaining to the regulation of outer space activities, the authors suggest the strengthening, clarification and expansion of the core principles of international space law that are promulgated in the five UN space law treaties.

In the space domain, it is not that law-making has completely come to a halt but it has significantly slowed to a level that will be unable to keep up with the pace of technological advancements and progress. In addition, the process of law-making in the form of binding commitments (including treaties) has shifted towards the adoption of non-binding guidelines and reports of groups of governmental experts, which are seen as the preferred mode of norm-making.

Recently, there have also been attempts at circumventing the United Nations process of law-making and an alarming trend of unilateral actions of some advanced spacefaring States, often to the detriment of multilateralism, and away from international measures and safeguards which ensure the protection and enhancement of the collective and inclusive interests of humankind.

The significant impact that space activities have on life globally makes the space domain a critical infrastructure both at national and international levels. It is, therefore, crucial for the international community, acting collectively and preferably through the UN system, to place high value and emphasis on the need to expand and update international space law, to enhance space law capacity-building, and to underline and place emphasis on the communal benefits of space for all.

There is a need for a more holistic approach to the adoption, coordination and application of international space treaties

There is a need for a more holistic approach to the aoption, coordination and application of international space treaties as well as national laws and regulations pertaining to space activities. It is therefore imperative that the global governance regime for outer space must be devised and developed on a multilateral, comprehensive, coordinated and regular basis. This can only be achieved through an intergovernmental organisation dedicated to space affairs.

Only such an international body could effectively and routinely address regulatory requirements of the day as well as the needs of the future to ensure the widespread and international acceptability and implementation of laws that enhance the collective interests of all States and all of humanity.

It is therefore suggested that there should be a specialised agency of the UN charged with the task of expanding and strengthening the global space governance framework, actively facilitating the progressive development of international space law and overseeing its effective implementation.

In addition to the issues of space militarisation and weaponisation, congestion and concerns about space debris, numerous other issues will need to be addressed. Such issues include matters related to planetary protection, planetary defence, cybersecurity, space weather, space transportation systems, standardisation of space ports, space traffic management, space travel and tourism, threats to dark and quiet skies, technical assistance to developing countries and emerging spacefaring States, the equitable sharing of space benefits, and the need to protect the interests of various human cultures, especially indigenous cultures and those that are on the verge of extinction. This also will potentially require concerted action by this proposed organisation, in cooperation with other appropriate international, regional and local institutions and the private sector.

Every aspect of each space activity or space-related issue need not be regulated by binding international treaties, but it is equally true that every such activity or issue cannot and must not be governed only by soft law (non-binding) instruments such as guidelines, United Nations General Assembly resolutions, transparency and confidence building measures, norms, etc.

While international law, international relations and conduct are a product of the times we live in, the collective human consciousness pertaining to our space ambitions and goals, expressed in the five UN space treaties, must be expanded and strengthened enough to survive the current onslaught of unilateralism and worrying trends that are threatening to accelerate an end to international space law.

There should be a specialised agency of the UN charged with the task of expanding and strengthening the global space governance framework

It is difficult to highlight or present a single event or even a chain of events that started a trend towards States disregarding international space law. Likewise, it is equally difficult to mark the exact time period that indicates the beginning of the end of international space law. Nonetheless, it is believed that the ‘beginning’ of the end of international space law has already occurred and continues unabated. In using the phrase “beginning of the end,” the authors do not in any way imply that an end is not stoppable or is inevitable. Rather, it is an urgent call to the international community to take appropriate actions and timely recourses.

If the rule of law is allowed to end or be significantly weakened in the space domain, the freedom of exploration and use of outer space by all, without discrimination of any kind and on a basis of equality, will significantly diminish, and threaten our common future, and humanity’s survival in the long term. The time to act is now, for the future of young people as well as that of their children or grandchildren, on the Earth but also in outer space and on the Moon and other planets.

Editor’s note

This article is an edited version, used with full permission, of a chapter contributed by Ram S. Jakhu and Nishith Mishra to the book Human Flourishing: The End of Law, Essays in Honour of Siegfried Wiessner, edited by W. Michael Reisman and Roza Pati, and published by Brill Nijhoff in November 2023. ISBN: 978-90-04-52482-8.

About the authors

Prof Dr Ram S Jakhu is Full Professor and former Director of the Institute of Air and Space Law and the Center for Research in Air and Space Law of McGill University, Montreal, Canada. He is also Project Director of the McGill Manual on International Law Applicable to Military Uses of Outer Space (MILAMOS), and author of numerous books and papers.

Nishith Mishra is a Doctoral Candidate and Research Assistant, Institute of Air & Space Law, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.