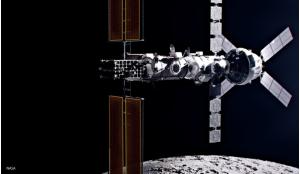

The way we relate to the Moon has failed to keep up with the pace of technological change. The general public and the space industry have become used to seeing the Moon as a dead rock, while the Committee on Space Research’s Planetary Protection Policy has no requirement to protect the Moon as there is no life there. But with proposed missions planned to establish a more permanent habitat, extract local resources and potentially use these to explore Mars, perhaps it is time to rethink old attitudes towards the Moon?

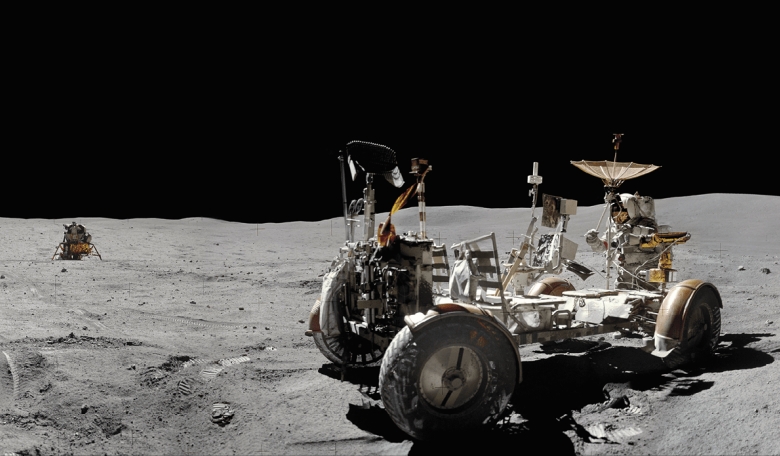

The Moon is more than the driver of Earth’s tides, a distant lamp illuminating our nights or a bundle of resources, such as water-ice and rare-earth elements. It is a complex planetary environment with an exosphere, a water cycle and a slow but constant geological process of dust interaction with cosmic rays and micrometeorites. As the Apollo missions of the 1960s showed, each landing location had its own unique landscape. In contrast to its monotonous grey, astronaut Alan Bean used his artist’s eye to show us a coloured Moon with mauves and yellows - a different palate from Earth’s with a unique aesthetic quality.

At the lunar poles are even more extraordinary landscapes, the likes of which do not exist on Earth and, indeed, in few other places in the solar system. The cratered terrain is formed from what have been called ‘craters of eternal darkness’ and ‘peaks of eternal light’. Within the craters are shadowed areas two billion years old that protect water-ice. No sunlight has ever grazed these frozen pools; starlight is the only illumination they have ever experienced.