Casual observers or those new to space can be forgiven for thinking there is a new scramble over the domination of outer space, or that the militarisation or weaponisation of space are novel, unprecedented issues. According to more dramatic and alarmist opinions, it is a reflection of a so-called ‘great power competition’ that may possibly extend to the Moon as US-Russian-Chinese relations sour. For many, ‘space’ conjures majestic images of the planets, stars and nebulae, the Apollo Moon landings, Martian rovers, or guitar-wielding astronauts on the International Space Station. These encapsulate space as a realm where humans work together in the pursuit of knowledge for the common benefit of humankind. Yet these feats of science and space exploration, which inspire many, are only the tip of the iceberg of a 70-year-long militarised Global Space Age. Robotic adventures on the Moon or astronauts on rival space stations are high-profile scientific or exploration activities that have little bearing on terrestrial military power today.

High-technology economic, industrial and military power rely on thousands of satellites orbiting Earth, owned or operated by over eighty countries or companies registered within them. This is not something that happened overnight. Military and intelligence space programmes, such as spy satellites and military satellite communications systems, have been deliberately hidden for most of our ‘Global Space Age’. Seventy years of techno-industrial competition in the global space sector has been known to only those inside it and to liberal arts and humanities academics who cared to look for it.

Publicly-released satellite imagery of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 demonstrated spy satellite technologies to mass audiences that governments and militaries have enjoyed for decades. In Original Sin - Power, Technology and War in Outer Space, I try to expose what has long been a secretive and niche area of expertise to a much wider audience, and show what the growth of technological infrastructures, military power and economic competition in space means for the practice and study of International Relations (IR) today. Space is not some new environment that transforms our social and political world, or somewhere that we cannot apply our terrestrial political concepts and practices.

Thousands of the satellites orbiting Earth are small, like the BIRDS-3 project CubeSats seen here being released from the International Space Station. The project uses a constellation of three 1U CubeSats developed by Japan, Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Thousands of the satellites orbiting Earth are small, like the BIRDS-3 project CubeSats seen here being released from the International Space Station. The project uses a constellation of three 1U CubeSats developed by Japan, Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Space is not a new or emerging military and security issue. Earth orbit has always been a place of military exploitation and economic competition since satellites began flying above the atmosphere. The ‘militarisation of space’ is not a new trend in world politics in the 21st century – it is a long-established historical fact and present reality.

Military infrastructure and spy satellites in orbit are now among the more important techno-geographic, physical and material aspects of international relations. ‘Spacepower’ is now an important provider and instrument of state and military power, just like seapower and airpower. Spacepower is the use and denial of thousands of machines in Earth orbit that provide important data gathering and communications services for governments, militaries, and economic infrastructure on Earth itself.

The ‘militarisation of space’ is not a new trend in world politics in the 21st century

Spacepower is pursued by states for the purposes of war, development and prestige, meeting specific needs and goals because the expense and difficulty of space activities require huge resources marshalled by a central authority. The Global Space Age has seen the creation of multiple technological infrastructures that many states have spent decades building to make their military forces more effective and high-technology economies more competitive today.

The political reality of outer space is at odds with the spirit of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which declares in Article I that “the exploration and use of outer space… shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind”. The reality is that space technologies have been developed by specific people, countries and organisations for a mixture of reasons, including self-serving ones, and some people have benefitted whilst others have suffered from or been threatened by them.

Publicly-released satellite imagery of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 demonstrated spy satellite technologies to mass audiences that governments and militaries have enjoyed for decades. Here Earth observation satellites captured a 40-mile-long Russian military convoy approaching Ukraine’s capital Kyiv on 28 February 2022.

Publicly-released satellite imagery of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 demonstrated spy satellite technologies to mass audiences that governments and militaries have enjoyed for decades. Here Earth observation satellites captured a 40-mile-long Russian military convoy approaching Ukraine’s capital Kyiv on 28 February 2022.

The era of ‘astropolitics’ as a specialist field of study and activity has long since arrived. Astropolitics refers to the political aspects of any activity in or to do with outer space. No activity escapes politics, not even international cooperation in space science. Who cooperates with whom, why, and on what terms is political and not necessarily something that happens for purely selfless reasons.

Though, looking at the scholarly field of International Relations, it does not feel like we are living in a space age. Humanities and social science research on space remains a very niche field, even though IR scholar Michael Sheehan explained in 2007 that “space and politics are, and always have been, inseparably interlinked.

“Politics has always been at the heart of humankind’s exploration and utilisation of space, and the space programmes themselves have never been able to transcend terrestrial international politics”.

US astronaut, Kevin Ford Canadian Space Agency astronaut Chris Hadfield and Russian cosmonauts Roman Romanenko (with camera) and Evgeny Tarelkin aboard the International Space Station on Christmas Eve 2012. But images such as this, that encapsulate space as a realm where humans work together in the pursuit of knowledge for the common benefit of all humankind, have little bearing on terrestrial military power today.

US astronaut, Kevin Ford Canadian Space Agency astronaut Chris Hadfield and Russian cosmonauts Roman Romanenko (with camera) and Evgeny Tarelkin aboard the International Space Station on Christmas Eve 2012. But images such as this, that encapsulate space as a realm where humans work together in the pursuit of knowledge for the common benefit of all humankind, have little bearing on terrestrial military power today.

Questioning why some countries develop their own space systems rather than relying on another’s is an astropolitical matter. To study astropolitics is to investigate behaviour and its consequences in outer space according to political and social concepts, and not simply recounting the partisan politics of a legislature that factors space into policy-making. A space policy of any kind is political.

Recognising the impacts of space on people, societies and polities, good and bad, is political analysis. Astropolitics therefore looks at the ‘why’, ‘should’ and ‘so what’ kind of questions that space activities pose, not the relatively simple technical questions of whether something ‘can’ be done.

Space is not just for the scientists – we need to discuss the political, strategic, and social causes and consequences of our Global Space Age.

Earth orbit has always been a place of military exploitation and economic competition since satellites began flying above the atmosphere

Space technologies were and are developed to meet military-political objectives. In Christian theology, original sin refers to “both the first historical sin of humankind and the bondage to sin that afflicts all of humankind thereafter”. Space systems – rockets, satellite constellations, their ground infrastructures and peripherals on Earth – have not escaped their militarised and competitive origins, or original sin. Yet we need not accept a fatalist, doomed or cynical future only redeemable by a divine entity as some Augustinian Christian doctrines might suggest.

For those wishing to transform things or prevent them getting any worse, a realistic assessment of the political and military origins and interests in space technologies must be the starting point. Political reform cannot happen without understanding past and present political reality in space.

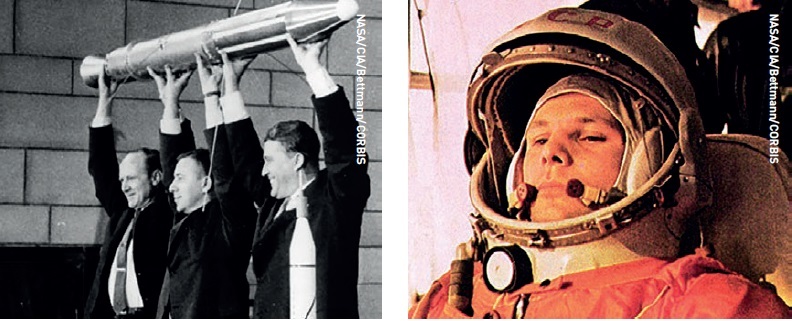

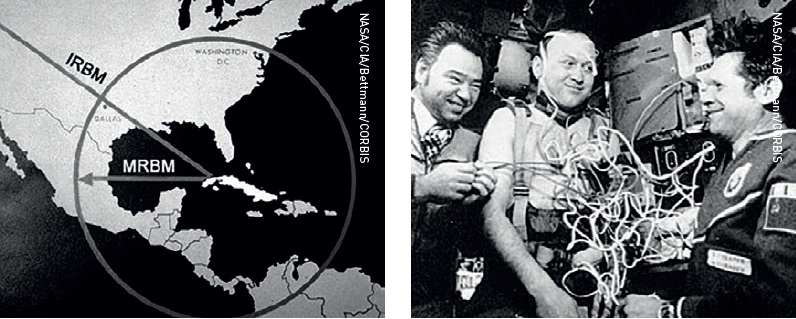

The biggest stain on benign images of space technology and the Space Age is that it helped bring about the prospect of nuclear Armageddon.

The satellite and Moon races of the 1950s and 1960s were in part deliberate covers for developing essential military space technologies such as more capable missiles, nuclear warheads, and spy satellites.

Professional communities refer to the civil and military uses of such technologies as ‘dual use’, and the multiple uses of base technologies are as common in space as they are on Earth. Yet much of the original technological drive was military, with civil and commercial applications developed afterwards.

The satellite and Moon races of the 1950s and 1960s were in part deliberate covers for developing essential military space technologies such as more capable missiles, nuclear warheads and spy satellites.

The satellite and Moon races of the 1950s and 1960s were in part deliberate covers for developing essential military space technologies such as more capable missiles, nuclear warheads and spy satellites.

The US Space Shuttle was in part originally designed and funded to meet the Pentagon’s and the Intelligence Community’s needs. The Hubble Space Telescope is an adapted KH-11 spy satellite that simply looks to the cosmos rather than down on Earth. The International Space Station was a product of intense political bargaining between the US, Europe, and Japan, and included Russian deal-making on missile technology export controls which tore up a prior Soviet-Indian rocket engine sales agreement.

Civilian and military space agencies often cooperate on major projects and activities and personnel move from one side to another. On the ground, many space powers benefitted from previous imperial and colonial conquests. Imperial territories became home to satellite control systems and launch sites.

The anarchy of the international system of space-faring states that compete militarily among themselves exists in space as the tethers of modernity have reached into Earth orbit; it is not some distant dystopian vision of the future. Without a supreme authority above them, the major states and most powerful governments of Earth use space to meet their own goals, check the interests of others, and impose their own influence on others where possible.

The economic system dominating Earth depends on several thousand active satellites in orbit, along with the elaborate terrestrial infrastructure that supports it all. Satellites provide a large range of communications and data-gathering services that make modern military forces more lethal and capable, economies more efficient, lucrative, and digital, and provide a number of critical infrastructure services such as weather, climate, and agricultural monitoring systems.

Many newcomers to space industries are developing their own military or economic space systems or partnerships on the global marketplace, keen to take advantage of, and trying not to be taken advantage by, these ethereal tethers of modernity that reach up to 40,000 km above Earth. Much of this has gone unnoticed not only by the public but by many scholars in the study of International Relations, as “infrastructure is boring, even when it is civilian and open. One only notices its absence when it does not work.” [Neufeld, Cold War - but no war - in space]

The political reality of outer space is at odds with the spirit of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty

Spacepower has gone from warning and targeting systems in nuclear war to an infrastructure that is relevant to any kind of conventional warfare and counterinsurgency on Earth, for developed and developing states and their armed forces alike. Plugging space technologies into terrestrial military power ensures that there are sound strategic reasons for many states to develop anti-satellite weapons and other methods of disrupting and harassing space infrastructure. In many ways the 2010s picked up where the superpowers left off in the 1980s with an increased tempo of anti-satellite weapons development and testing.

Despite this, space warfare is yet to be normalised in many professional quarters. Space warfare instead tends to be spoken of as a subset of nuclear war, deterrence or ballistic missile defence which impose their own analytical blinkers on what spacepower is doing to military power.

Space warfare should be approached in the same way we think about naval warfare, aerial combat, and how seapower and airpower contribute to modern strategy and military, economic and political power. It should be approached as a geographic specialism of warfare in a place that resembles a coastal zone between places more than it does the ‘ultimate high ground’ or the open ocean.

Such fighting is done to impact the control and denial of space infrastructure. Its logistical impacts tend to impose the effects of dispersion on the modern battlefield and force postures. As space is now so useful in almost any high-technology activity, the spectre of space warfare will likely stalk the 21st century and beyond.

Editor’s note: this article is based on an extract from Original Sin - Power, Technology and War in Outer Space published by C Hurst & Co (Publishers), 2022. (ISBN: 9781787387775). The extract, for which bibliographical references have been removed, has been edited and amended for standalone publication.

Editor’s note: this article is based on an extract from Original Sin - Power, Technology and War in Outer Space published by C Hurst & Co (Publishers), 2022. (ISBN: 9781787387775). The extract, for which bibliographical references have been removed, has been edited and amended for standalone publication.

About the author

Dr Bleddyn Bowen is Associate Professor of International Relations at the University of Leicester, an expert in strategy, space warfare and the military uses of outer space, and the author of War in Space: Strategy, Spacepower, Geopolitics and several papers on space policy in a variety of academic journals. Dr Bowen frequently appears in media items on space policy and advises practitioners on space security and defence policy in space.