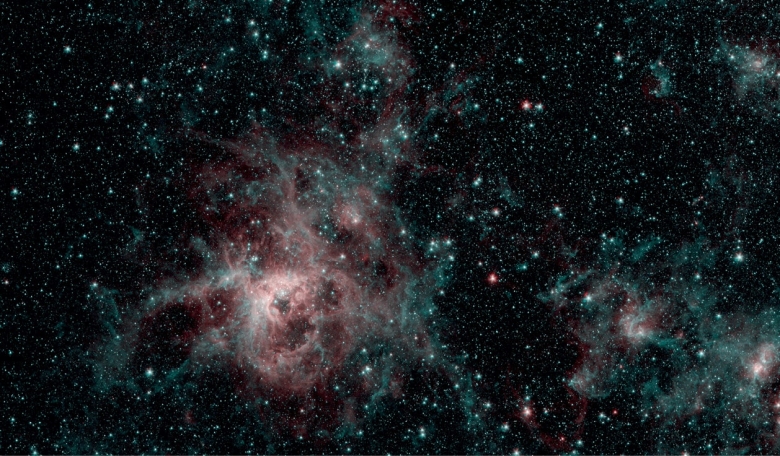

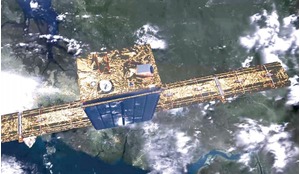

The Spitzer Space Telescope is the final mission in NASA’s Great Observatories programme, a family of four space-based telescopes, each designed to observe the universe in a different waveband. Spitzer was launched in 2003 and, having exceeded its design lifetime by 14 years, was retired in January 2020. The telescope observed in the infrared and for the first five-and-a-half years operated at close to absolute zero in what became known as its ‘cold mission’. The ‘warm mission’, which began when the liquid helium supply was exhausted, was conducted at 30 Kelvin (approximately -243C). Scott Tennant, programme manager at Ball Aerospace in Colorado, USA, has worked on all four of NASA’s Great Observatories - Hubble, Compton, Chandra and Spitzer – which gives him a fairly unique perspective on space science. ROOM’s US editor, Amanda Miller, delves into his engineering background and the key technologies of the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Your career at Ball Aerospace dates back to the early days of space telescopes and you have worked your way up to senior programme manager. Can you tell us a bit more about your early work on space telescopes?

My first job at Ball, in the mid-1980s, was on the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), an early infrared observatory and a kind of precursor to Spitzer. We knew we had to cool the telescope’s detector, to allow us to detect the very weak infrared signals, but we couldn’t get it as cold back then as we can now with superfluid helium. After IRAS, I worked on the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE), which was another smaller, pathfinder type of spacecraft.