Growth is not without its consequences and the upcoming anniversary of the Outer Space Treaty presents an opportunity for the global community to reflect not only on what has been achieved in the past half-century but also on the collective path forward into the future.

This article highlights space debris, a specific aspect of growth in space activities that affects everyone who derives benefit from the final frontier. It will attempt to elucidate the complex nature of legal aspects surrounding debris that currently pre-occupy space lawyers but will ultimately provide more questions than answers. Questions that merit, or even require, broad and careful consideration by all stakeholders in outer space.

Space debris, or orbital debris, comprises man-made objects that range in size from miniscule flecks of paint to entire defunct satellites. It is a by-product of normal space activities or the disintegration of objects in space through collisions, or even anti-satellite weapons.

Graphical rendition of a larger piece of debris in orbit - if not passivated such a spent upper stage can carry risk of explosion and fragmentation

Graphical rendition of a larger piece of debris in orbit - if not passivated such a spent upper stage can carry risk of explosion and fragmentation

In both the immediate and mid-term, a growing debris population in near-Earth orbit poses a significant threat of damage or destruction through collision to operational satellites, and to human life in space or on the ground. Longer term, space debris endangers the sustainability of outer space activities and the use of the space environment itself by reducing Earth orbit to inhospitable debris belts [2].

Although scientific predictions on the space debris environment based on sophisticated modelling techniques and real-time observations carry a degree of uncertainty, the scientific and technical community agrees that concerted action is needed on multiple fronts to slow down or even reverse the proliferation of hazardous orbital junk. Enter the space jurist.

Legal conundrum

At first glance, the traditional legal avenue of devising and applying rules and regulations seems an apt way to mollify the problem. However, this approach must contend with the unique physical and legal reality of outer space that produces significant hurdles to the creation of broad legal frameworks that are both effective and feasible.

Emerging space-faring States are wary of binding regulations which could unfairly limit their legitimate expansion into outer space while not yet having contributed directly to the space debris problem

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, ratified by 104 States, is still highly relevant today and is, together with four other United Nations (UN) treaties on outer space, the predominant instrument that structures international space law. It can be considered a constitution of sorts for space jurists, by which all national and international legal advancements on space activities must be measured and weighed.

Its importance cannot be overstated - but its grand visionary scope combined with its inception in an era of only nascent space activities, creates difficulty in deftly addressing more detailed legal questions that are only now coming to the fore.

A fundamental and abstract legal matter in this regard, that appears almost too simple and too basic to present an obstacle, is the question: what is space debris? Technical definitions used by scientists and engineers, as well as in the technical and non-binding Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines [3] of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UN COPUOS) focus unvaryingly on the non-functional nature of debris: space debris are all man-made objects, including fragments or elements thereof, in Earth orbit or re-entering into Earth’s atmosphere that are non-functional.

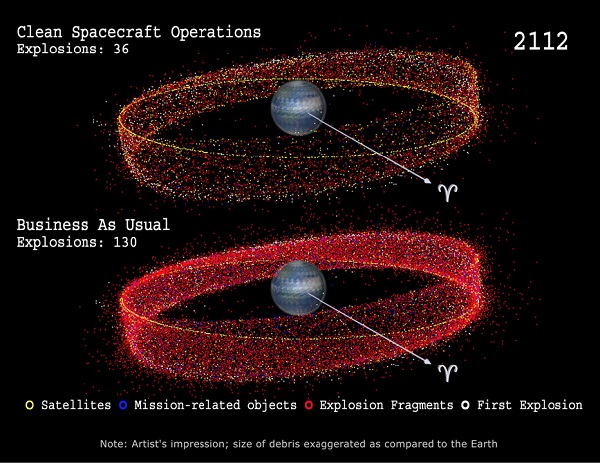

Diagrammatic simulation of the future geostationary environment in the case when no measures are taken (‘business-asusual’). In the top panel, with mitigation measures, a much cleaner space environment can be observed - if the number of explosions is reduced drastically and if no mission-related objects are ejected. However, to stop the ever-increasing amount of debris, more ambitious mitigation measures must be taken. In the long run, spacecraft and rocket stages have to be returned to Earth after completion of their mission

Diagrammatic simulation of the future geostationary environment in the case when no measures are taken (‘business-asusual’). In the top panel, with mitigation measures, a much cleaner space environment can be observed - if the number of explosions is reduced drastically and if no mission-related objects are ejected. However, to stop the ever-increasing amount of debris, more ambitious mitigation measures must be taken. In the long run, spacecraft and rocket stages have to be returned to Earth after completion of their mission

However, this definition, intuitive as it may be, cannot easily be construed into an international legal definition. The existing space law treaties simply do not mention ‘space debris’ anywhere. The closest related, applicable and rather vague term in the treaties is that of ‘space object’. The treaties apply this term to any object launched into space to determine important legal consequences such as which State has sole jurisdiction and control over the object, which State can register the object or which States are liable for damage caused by the object in space or on Earth.

Nevertheless, the treaties do not define what exactly is a ‘space object’ and, more importantly, they do not consider the functional or non-functional nature of the space object in applying these important legal consequences to it.

Unauthorised targeting or removal of a space object could create hostile conflict or contribute to an atmosphere of escalatory competition in offensive removal capabilities

Therefore, international space law does not contain any provisions that could form the basis for a legal distinction between valuable spacecraft and supposedly worthless space debris. Faced with this legal uncertainty, the majority of legal experts appear to agree that even if a satellite were to become non-functional or to catastrophically break up into separate fragments, these will still constitute a ‘space object’ for the purposes of the treaties and carry with them all legal ramifications thereof.

The Outer Space Treaty declares that any State that has registered a space object shall retain legal and de facto jurisdiction and control over that object. As a piece of space debris is considered a ‘space object’ for legal purposes, even if the State were to lose de facto control over the space object when it becomes non-functional or uncontrollable, it retains sole legal jurisdiction and control as per the treaty. Therefore, it is uncertain whether space objects, their component parts or fragments thereof can legally be abandoned or considered abandoned, irrespective of their non-functional status.

This notion is reinforced by the fact that space faring States have hitherto not expressed a right to abandon their non-functional satellites in space. This sheds severe doubt on the possibility of introducing a legal regime of ‘salvage’, similar to maritime law, whereby actors other than the State of registry could freely remove pieces of debris that pose a threat in Earth orbit.

The way forward

As many in the field of international space law have called for, solace for this conundrum and other problems related to space debris may be partially sought in the introduction of some kind of legal criterion of non-functionality into space law to differentiate between valuable space objects and simple debris.

The proverbial fly in the ointment is who can - or must - decide, and on what grounds, when exactly a space object ceases to be functional or can be targeted for removal. For example, is a satellite that has become damaged or uncontrollable but still retains some of its intended capabilities non-functional? What about a seemingly non-functional but unitary satellite that is merely in a state of hibernation and represents a potential back-up capability for its State of registry? Moreover, is it agreeable that orbits that are at a premium can be occupied indefinitely by ‘space objects’ that may or may not be functional?

Currently and up to a point, these questions can be answered through application of the current treaties. A State of registry could offer unambiguous and prior authorisation to another party to undertake removal of its space object, a notion that is currently being explored in UNCOPUOS in the draft guidelines on the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities [4].

In both the immediate and mid-term, a growing debris population in near-Earth orbit poses a significant threat of damage or destruction

This option is especially relevant in light of the dual-use nature of removal technology: unsolicited or unauthorised targeting or removal of a space object by a third actor could create hostile conflict in space or on Earth, or contribute to an atmosphere of escalatory competition in offensive removal capabilities that leads to an arms race in outer space.

Naturally, a State can also freely choose to deem non-functional and remove its own space objects. But why would it do so in light of the potentially gargantuan international legal responsibility and liability for damages when something goes awry in the application of highly novel and hazardous removal technology when there is no legally enforceable obligation?

Finally, what about smaller fragments of space debris that, in contrast to largely intact objects, are mostly not identifiable and cannot be attributed to a State or cannot even be adequately tracked?

Often, no authorisation can be sought to remove these objects as there is little or no incentive for States to claim them as their own or an appropriate State cannot be identified. Otherwise, separate and prior authorisation would have to be concluded for an innumerable amount of small debris; an impossible task. Thus, it would be as remiss to place these small objects under the same uniform category as large, identifiable space debris as it would be neglectful to forget about them outright. But how do we delineate between these different types of debris? Do we introduce a legal presumption that certain objects are debris according to size, volume or weight? Where do we draw the line? The recent surge in cubesat and miniaturisation technology is bound to further muddy the legal waters.

A road travelled together

To conclusively deal with these and other important legal issues related to debris and active debris removal, various States, legal scholars, international organisations and non-governmental organisations have called for a new, binding treaty on space debris, or for clarifying binding protocols to the existing treaties to be promulgated after careful deliberation between States in UNCOPUOS.

However, there has been a clear reluctance to conclude binding legal instruments within UNCOPUOS over the past decades and the process is slow in any case. As an indication, the subject of space debris, including possible mitigation measures, was first put before the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee in 1980 [5] after which it took nearly three decades for mitigation measures to be formalised in the merely non-binding and voluntary UNCOPUOS Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines of 2007. What causes this international lethargy?

Treaties do not define what exactly is a ‘space object’ and, more importantly, they do not consider the functional or non-functional nature of the space object

Established space powers seek primarily to draft non-binding, voluntary instruments of soft-law in UNCOPUOS as these, ostensibly, do not impede their hitherto largely unfettered freedom of action and dominance in outer space.

Meanwhile, emerging space faring States are wary of binding regulations as they feel these could unfairly limit their legitimate expansion into outer space while they have not yet contributed directly to the space debris problem.

Additionally, UNCOPUOS itself, the predominant forum for negotiations on new instruments of international space law, operates on the principle of consensus. As membership is relatively easy to obtain it has grown to 77 member states, all with disparate national interests, and provides an opportunity for leverage on unrelated geopolitical matters. Lastly, private actors, industry and business do not have a direct seat of their own at the negotiating table, thereby silencing an important stakeholder at the highest level of deliberation.

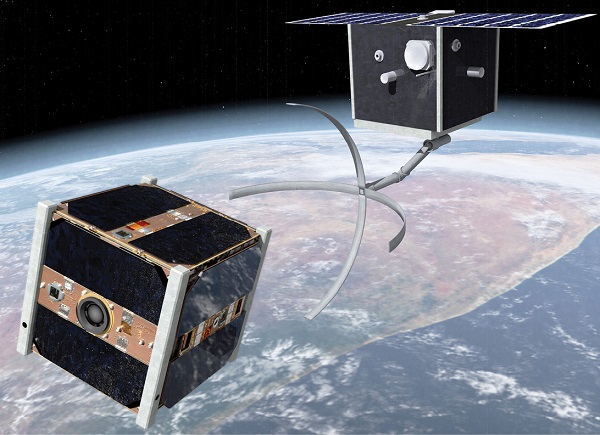

Potential design for CleanSpace One’s active debris removal technology demonstration mission in which they will attempt to capture the Swisscube spacecraft and clean it up. Swisscube has narrowly avoided impact several times - soon after launch it was caught up in the train of debris created by the February 2009 collision between the commercial satellite Iridium-33 the Russian satellite Cosmos-2251; in September 2013, the US Air Force reported the Cubesat had passed less than 75 m away from one of 15,000 pieces of space debris more than 10 cm in diameter that have been identified and are monitored from the ground by the US. Barring an unforeseen event, Swisscube’s demise has been programmed for 2018. It will be the first object captured and destroyed by CleanSpace One, a space debris clean-up satellite currently under development

Potential design for CleanSpace One’s active debris removal technology demonstration mission in which they will attempt to capture the Swisscube spacecraft and clean it up. Swisscube has narrowly avoided impact several times - soon after launch it was caught up in the train of debris created by the February 2009 collision between the commercial satellite Iridium-33 the Russian satellite Cosmos-2251; in September 2013, the US Air Force reported the Cubesat had passed less than 75 m away from one of 15,000 pieces of space debris more than 10 cm in diameter that have been identified and are monitored from the ground by the US. Barring an unforeseen event, Swisscube’s demise has been programmed for 2018. It will be the first object captured and destroyed by CleanSpace One, a space debris clean-up satellite currently under development

To be sure, all of the above are important considerations and will have to be resolved before a coherent and feasible international legal framework that offers certainty on and a solution to space debris can be constructed - but the international community is far from helpless in the interim.

States and industry can freely enjoin in depoliticized, international cooperation and transparently decide between themselves which objects are space debris, who will peacefully remove them and how the financial burden and potential for liability is to be shared.

The collective trust, knowledge and experience gained can then be put towards more effective future international legal instruments on space debris and active debris removal with global support. In so doing, there is an opportunity to collectively create new space law that is suitably adapted to the challenges of the 21st century and to still hold true to the visionary principles of the original Outer Space Treaty that space shall be the province of all mankind. After all, we are all in this together.

References

1 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (Outer Space Treaty), adopted on 19 December 1966 and entered into force on 10 October 1967, Resolution 2222(XXI) of the United Nations General Assembly, Annex, International Legal Materials 1967, Vol. 6, 386-390.

2 The term Kessler Syndrome, named after Donald J. Kessler who first alerted to this devastating potential of debris proliferation in 1978, denotes a runaway cascade effect wherein collisions between a growing number of orbital objects, debris or spacecraft, will create more debris and lead to more collisions, ad infinitum. See: D.J. KESSLER and B.G. COUR-PALAIS, “Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: The Creation of a Debris Belt”, Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 1978, 2637-2646 and D.J. KESSLER, N.L. JOHNSON, J.C. LIOU and M. MATNEY, ‘The Kessler Syndrome: Implications to Future Space Operations’, Advances in the Astronautical Sciences 2010, 47-61.

3 Report of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space on its fiftieth session (15 June 2007), UN Doc. A/62/20 (2007), §118-119 and Annex.

4 Updated set of Draft Guidelines for the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities (30 April 2015), UN Doc. A/AC.105/L.298 (2015).

5 Mutual relations between space missions (7 December 1979), UN Doc. A/AC.105/261 (1979).