Controversy has always surrounded the water content on Mars and while some claim it is responsible for carving out the largest canyon in the solar system, others have a more fiery explanation as to how many, if not all, of the great valley systems came about. If water is not as abundant as once thought, should we give up our plans to colonise the red planet?

The formation of the solar system was a chaotic period characterised by, amongst other things, impacts between planetesimals and growing planets. These impacts were somewhat random and occurred not only along the orbit that each planet swept but also in their polar regions.

Large southern polar impact basins such as the Aitken-South Pole on the Moon, Rheasilvia on Vesta, and the Martian dichotomy on Mars reveal that an important flux of impactors came from the southern side of the inner solar system. The collision responsible for the southern polar giant impact that formed the Martian dichotomy is the most peculiar because it did not leave a large depression, but instead produced a unique topography and volcanism never seen before in the whole solar system.

The large impactor that changed the face of the planet just four million years after Mars fully accreted - around 4.5 billion years ago — struck the red planet’s south pole at a speed of ~5 km/ sec. It is surmised that the object fits one of two descriptions; it either had a radius of approximately 1600 km (for comparison the radius of the Moon is about 1737 km) with an iron content of around 80 percent, or it was larger at 2000 km radius with a lower iron content (around 50 percent).

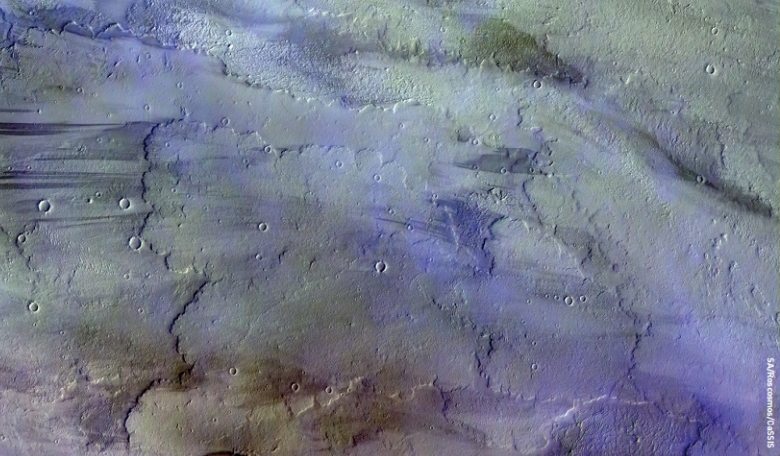

Either way, its sheer size meant that the impactor reached the core of Mars which resulted in the planet heating up to 2300 degrees Kelvin and turning the whole southern hemisphere of the planet into a magma ocean. The re-equilibration, cooling and subsequent solidification of this magma ocean deleted every trace of the impact and formed the Martian dichotomy that is seen today; a southern hemisphere characterised by highlands and a northern hemisphere identified by its lowlands. The cooling process also formed a thick crust in the southern hemisphere under which hot mantle plumes migrated towards the south pole giving origin to 12 alignments of volcanoes still visible on the Martian surface.

Find out more about Mars' fascinating history and the human search for water on the red planet in the full version of the article, available now on our website.