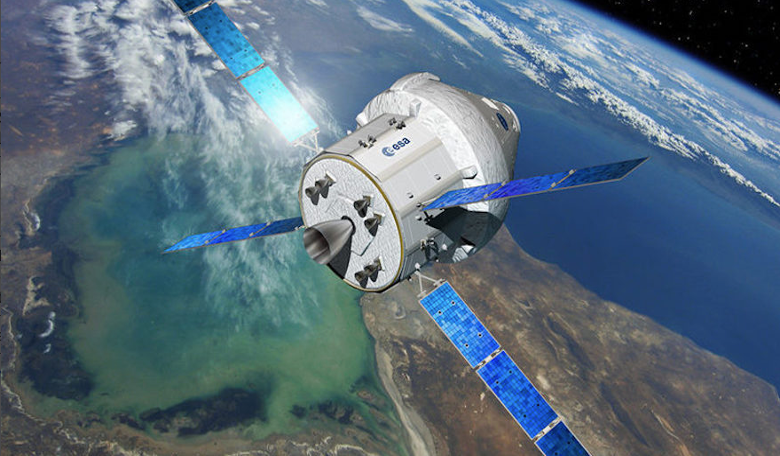

It has been years in the making, but the European Service module that will power NASA’s Orion spacecraft is finally ready to be shipped to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, USA where it will be put together with the rest of the Orion spacecraft. This is the first time that NASA will use a European-built system as a critical element to power an American spacecraft.

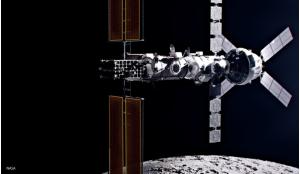

The Orion spacecraft, along with the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket that will carry it all into space, is NASA’s flagship programme to propel human exploration to the Moon and beyond.

The spacecraft, which consists of a launch abort system, a crew module and a service module, will serve as the exploration vehicle and it will carry the crew to space, sustain astronauts during their missions, provide emergency abort capability, and provide safe re-entry from speeds that can exceed 25,000 mph as astronauts return from deep-space missions.

Most of the operations required for day to day living, such as breathing and heating are provided by the Service Module, which sits at the base of the spacecraft. But the service module is also designed to provide in-space propulsion, attitude control, and high altitude ascent aborts should anything go wrong. And for additional storage (for space souvenirs perhaps?) it is also equipped with a stowaway compartment that can be used to store unpressurised cargo.

Despite its high degree of functionality, the service module is designed to be discarded at the end of each mission. The service module soon to be shipped to the US, will be used solely for NASA’s Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) – an uncrewed flight that will test the feasibility of sending astronauts into deep space. EM-1 will travel thousands of miles beyond the Moon – around 450, 000 kilometres (280,000 miles) from Earth – over the course of about a three-week mission and will stay in space longer than any ship for astronauts has done without docking to a space station.

If all goes according to plan, then the second flight (EM-2) will replicate the first test but this time with humans onboard.

Orion is slowly coming together piece by piece and in this last year a number of key milestones have been passed as the spacecraft works towards completion; last month, NASA completed the final test to its parachute system - a system that consists of 11 parachutes and has for example over 16 kilometres (10 miles) of suspension lines for the three main parachutes alone!

“We’re working incredibly hard not only to make sure Orion’s ready to take our astronauts farther than we’ve been before, but to make sure they come home safely,” said Orion Program Manager Mark Kirasich. Once deployed, Orion’s 11 parachutes will slow the crew module to a landing speed of 27 kilometres per hour (17 miles per hour) to ensure a safe landing for astronauts returning to Earth.

And if that landing happens to take place in the ocean, NASA has been working with the Department of Defence to perfect their sea-recovery procedures and skills so that they can pick-up the crew as quickly as possible.

“We are testing all of our equipment in the actual environment we will be in when recovering Orion after Exploration Mission-1,” said Melissa Jones, NASA’s recovery director. “Everything we are doing today is ensuring a safe and swift recovery when the time comes for missions with crew.”

Flight controllers have also conducted tests to ensure that Orion can communicate successfully with mission control through NASA’s satellite network in space and the spacecraft’s heat shield that will protect the crew module from the scorching 5,000 degree heat it will experience as it plummets back to ground through Earth’s atmosphere, has also been recently installed.

But with less than two years to go before the anticipated launch date of EM-1 (June 2020), there is still a lot left to do to get the mission space-ready.

Meanwhile, back in Bremen, work is already underway by ESA on the second European Service Module that will keep astronauts alive and well for Orion’s Exploration Mission-2 (EM-2).

Orion European Service Module during testing. Image: NASA

Orion European Service Module during testing. Image: NASA