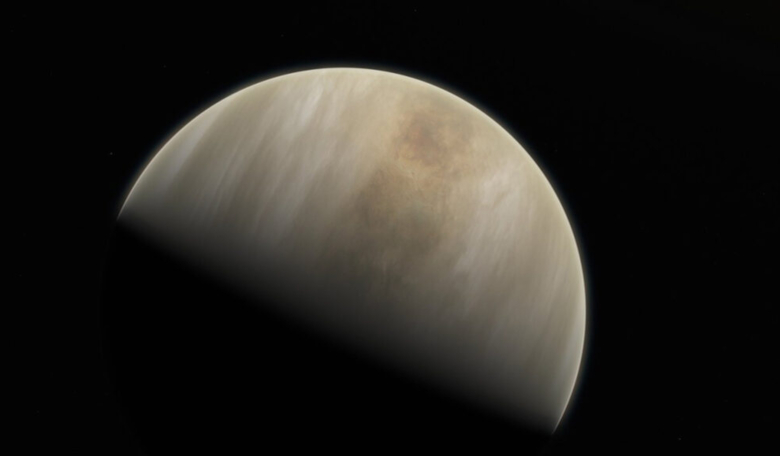

The ongoing debate as to whether signs of phosphine in Venus’ skies signalled the presence of microbes was dealt a serious blow last month when a new study suggested that life as we know it could not tolerate conditions among the planet’s sulphuric-laden clouds. Now another new study also dispels the notion of microbial life as it reports that volcanism on our planetary neighbour is enough to account for this intriguing gas signature – a finding which had previously been dismissed.

Last year, a colourless, flammable, very toxic gas compound with the chemical formula PH3 hit the headlines when it was discovered in Venus’ thick, hellish atmosphere.

It’s detection garnered huge interest as this simple molecule can only be produced on Earth artificially in a lab, or by bacteria and microbes that don't require oxygen to thrive, meaning that on Venus, it likely meant one thing – traces of life scattered throughout the planet’s clouds.

Another key method of producing phosphine is through chemical reactions between sulphuric acid and phosphides (P3−), which are brought to the surface by volcanism.

Recent studies suggest that Venus could still be volcanically active and that lava flows coating the surface may be only a few years old.

If so, this might account for the small amounts of phosphine found on the planet, but this hypothesis was rejected by some as it was deemed not enough of the gas could be produced this way to counter the rapid destruction of the compound in Venus’s highly oxidising atmosphere.

Now two Cornell scientists, Jonathan Lunine, professor of physical sciences and post doctoral candidate Ngoc Truong, say actually, there is enough evidence to support volcanoes as the source of phosphine on Venus.

Based on data collected from the ground-based, submillimeter-wavelength James Clerk Maxwell Telescope atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in northern Chile, the pair say that phosphides, bound in metals such as iron, are finding their way to the surface from deep within Venus’ interior by plume volcanism.

Volcanic plumes on Earth are mixtures of volcanic particles, gases, and entrained air that are produced by explosive eruptions.

Material from the plumes can be injected to high levels in the atmosphere and dispersed on a global scale - a process that is happening now or Venus’ recent past say Lunine and Truong.

One released by explosive volcanic eruptions, the phosphides then react with the Venusian atmosphere's sulfuric acid to form phosphine.

"The phosphine is not telling us about the biology of Venus," said Lunine, chair of the astronomy department at Cornell. "It's telling us about the geology. Science is pointing to a planet that has active explosive volcanism today or in the very recent past."

The idea of explosive volcanism on Venus is backed up by radar images from the Magellan spacecraft in the 1990s which shows some geologic features supporting this theory say Lunine and Truong.

In addition, scientists working on NASA's Pioneer Venus orbiter mission in the 70s, uncovered variations of sulfur dioxide in Venus' upper atmosphere, hinting at the prospect of explosive volcanism; a mechanism that was behind the enormous Krakatoa volcanic eruption in Indonesia in 1883 Truong said.

This eruption was so violent, the explosions were heard as far away as Perth, Western Australia 3,110 kilometres (1,930 miles) away.

Lunine and Truong note that the phosphine detection that sparked the initial life on Venus frenzy is still the subject of a lot of debate, but should this controversial gas be there, then “confirming explosive volcanism on Venus through the gas phosphine is totally unexpected”, Truong said.

The duo’s study, "Volcanically Extruded Phosphides as an Abiotic Source of Venusian Phosphine," has been published this week in PNAS.