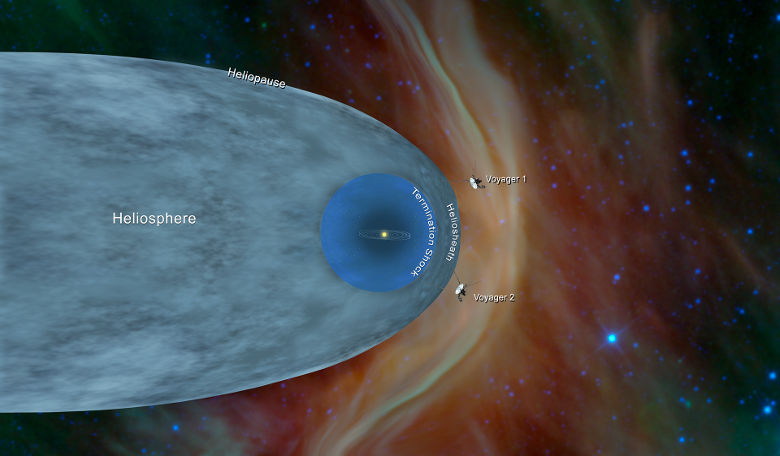

Going where only one other spacecraft in history has gone before, Voyager 2 crosses the protective bubble of the heliosphere surrounding the planets and ventures into the realm of interstellar space to join with its twin, Voyager 1.

The trailblazing spacecraft is now slightly more than 18 billion kilometers (11 billion miles) from Earth and amazingly mission operators can still communicate with the probe.

Evidence that Voyager 2 has left the heliosphere came from its onboard Plasma Science Experiment (PLS) which measures the electrical current of the plasma to determine the speed, density, temperature, pressure and flux of the solar wind. The heliopause is the outer edge of the heliosphere that separates this tenuous, hot solar wind from the cold, dense interstellar medium lying beyond.

As of 5 November, scientists noted a steep decline in the speed of the solar wind particles, followed by a lack of further data on the solar wind flow around Voyager 2 since that date. Coupled with measurements from the probes other instruments – the low energy charged particle instrument, the cosmic ray subsystem and the magnetometer – it was enough evidence to support the conclusion that Voyager 2 has crossed the heliopause into the unknown.

“Working on Voyager makes me feel like an explorer, because everything we’re seeing is new,” said John Richardson, principal investigator for the PLS instrument and a principal research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

The PLS instrument aboard Voyager 1 stopped working in 1980 long before that probe crossed the heliopause, but was believed to have crossed the boundary six years before its twin.

“Even though Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause in 2012, it did so at a different place and a different time, and without the PLS data. So we’re still seeing things that no one has seen before,” added Richardson.

Launched in 1977 (Voyager 2 launched 16 days before Voyager 1) and built to last just five years, the duo have surpassed all expectations since leaving Earth. After completing their original mission of closely inspecting Jupiter and Saturn, with fuel left in the tank, the probes were pushed on further to study the two outermost giant planets, Uranus and Neptune. Since then the two have been surveying all in their path as they continue on a most unexpected journey and now in their 41st year of operations Voyager 1 and 2 are NASA’s longest running mission.

However, despite now reaching where no person-made object has gone before, the probes have not yet left the solar system. The outer rim of the Oort cloud is considered to be where our Solar System comes to an end. This giant spherical shell surrounding the Sun, planets, and Kuiper Belt Objects stretches for around 100, 000AU. Given that one AU is the distance from the Sun to Earth, it will take about 300 years for Voyager 2 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly 30,000 years to fly beyond it; providing it doesn’t have a close encounter with an icy, rocky object big enough to take it out.

“I think we’re all happy and relieved that the Voyager probes have both operated long enough to make it past this milestone,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “This is what we've all been waiting for. Now we’re looking forward to what we’ll be able to learn from having both probes outside the heliopause.”