While much Western attention focuses on the space ambitions of traditional powers and emerging players, such the United Arab Emirates, one country has quietly but persistently advanced its space programme under intense international scrutiny and sanction. Iran, often cast in adversarial terms by the West, launched more satellites in 2024 than Europe. In this revealing analysis, veteran space writer Brian Harvey explores the evolution of Iran’s civil and military space capabilities, its complex international partnerships, and the strategic motivations driving its cosmic ambitions – many of which challenge long-standing global assumptions.

Iran has the distinction of being one of the most impressive, but least well known of the world’s new space powers. Indeed, a recent review, entitled ‘State of the space industrial base, 2024’ [New Space Nexus, 2025] considered New Zealand an emerging player, but not Iran.

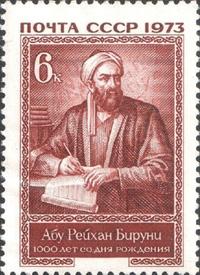

Iran was, like China, a scientific civilisation long before the spaceflight era. Its astronomical observatories can be traced to the fifth century BCE, while the Maragheh observatory (of 1259 CE) was famous for its observations, instruments and books. Iran gave us the great astronomer Al Biruni (973-1050) and Omar Khayyam (1048-1131), mathematician and algebrist and founder of Isfahan observatory. Iran now has 20 observatories, the most recent of which was added in 2022.

It may also come as a surprise that Iran was one of the first countries to join the Space Age, in 1957, when it established a Minitrack station to follow the American Vanguard satellite, and in 1958 co-founded the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Use of Outer Space (COPUOS).

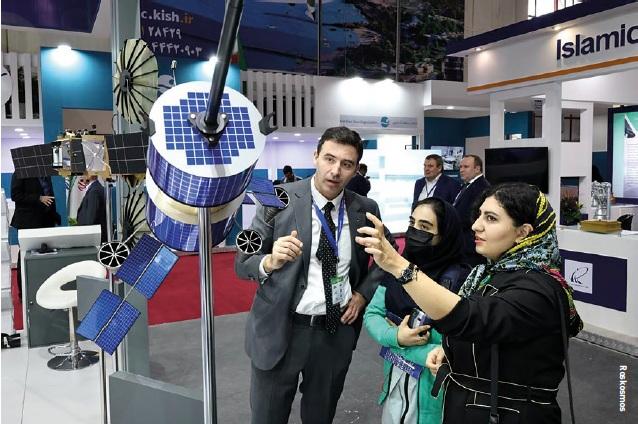

Iran’s space stand at the Kish Airshow in the Persian Gulf.

Iran’s space stand at the Kish Airshow in the Persian Gulf.

Also, like China, politics were not kind to Iran. Both endured western invasions and occupations for similar periods: China, from 1841 to 1949 and Iran from 1804 to 1946. The western-installed government of 1953 ensured that the early Iranian space programme was American, with ground stations built to listen in on the Soviet space programme from the south shore of the Caspian Sea (in 1956), access to Intelsat communications satellites (in 1969) and Landsat remote sensing (in 1972).

Iran was, like China, a scientific civilisation long before the spaceflight era

The Iranian revolution of 1979 was one of the largest popular revolutions in history, with millions involved across the political spectrum, and comparable in scale to those in France, Russia and China (in 1789, 1917 and 1949, respectively). Political turbulence followed and the universities closed from 1980-83. In fact, the US left its ground stations in such a hurry that the revolutionaries found the equipment ‘still humming’.

The subsequent political convulsion obscured the fact that a self-governing Iran now had the opportunity to undo the illiteracy of the Shah’s period and at last invest properly in education and science. In Iran today, 60 percent of university students are women, 70 percent of whom study science subjects.

In the violent upheaval that followed the revolution, the space programme was effectively on hold until President Muhammed Khatami took office in 1997. He asked Russia and China to launch its first satellites, set up the Aerospace Research Institute (ARI) with a space biology programme in 2000, the Iranian Space Agency (ISA) in 2005 and the Space Research Institute in 2007.

Achievements

Although Iran had been one of the first countries to come to American assistance after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the neoconservative revolution overwhelmed the White House and President Bush’s State of the Union address on 29th January 2002 declared Iran a founder member of the ‘axis of evil’. Thus, Iran found itself trying to continue its space programme under western siege and hostility, making its subsequent achievements all the more remarkable.

In effect, Iran developed four space programmes, the first three domestic: ARI’s space biology programme; the ISA civil programme; and a military programme run by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The fourth comprised Iranian satellites launched by other countries.

Domestically, ARI was first up on 4 February 2008, when the small Kavoshgar rocket launched the first suborbital payloads of up to 500 kg to altitudes of 130 km, variously carrying rodents, turtles, worms and monkeys.

Iran’s first satellite, Omid came not long after (on 2 February 2009), making Iran a space-faring nation, the ninth in the world, ahead of the two Korean states. Omid, meaning hope, was a small, 27 kg, ultra-high frequency store-and-forward communications satellite that transmitted for 50 days and decayed after three months. Omid demonstrated Iran’s ability to master all the subsystems required to make a functional domestic satellite and launch and operate it.

This set the pattern for five small communications and imaging satellites at varying intervals to the present, named Rasad, Navid, Fajr, Mehda and Fakhr, with two CubeSats, Hatef and Kaihan. However, Omid is still remembered and celebrated on National Space Technology Day, its launch date.

Iran was one of the first countries to join the Space Age, in 1957, when it established a Minitrack station to follow the American Vanguard satellite

Iran’s military programme was up next. Iran had originally acquired Russian-originated Scud missiles, based on the wartime German Wasserfall, using hypergolic, storable, nitric acid fuelled rockets, fired during the ‘war of the cities’ against Iraq (1986-88). Iran’s subsequent military programme went down a different route, developing a home-made solid fuel rocket, the Qased, which launched the first military imaging satellite series, Nour 1, on 22 April 2020, followed by Nour 2 and 3, military observation satellites and Chamran.

Iman Khomenei Launch Centre in Semnan Province.

Iman Khomenei Launch Centre in Semnan Province.

The fourth strand was Iranian satellites launched by other countries. Isolated by the west, Iran had turned to Russia and China even before Omid, and Russia had launched Iran’s first domestic satellite, Sina 1, on the Cosmos 3M from Plesetsk on 27 October 2005. Originally it was to be entirely home built, but it was completed in Russia. Next was the Earth resources satellite Huanjing 1A, launched by China on 6 September 2009. This was actually a joint project between China, Iran and Thailand though the Chinese said little about Iranian participation at the time. This omission didn’t do China any good, however, because the ever-alert Americans found out and, in reprisal, seized foreign assets of the Great Wall Industry Company which arranged the deal. Since then, Russia has launched four more Iranian satellites: Khayyam (named after the astronomer), Pars, Kowsar and Hodhod.

Iranian rocket engine.

Iranian rocket engine.

Infrastructure

Satellites are, of course, only the tip of the iceberg of any country’s space programme, which requires an infrastructure of rockets, launch centres, tracking stations and other facilities and institutes for scientific education. Iran has two launch centres: one civil, one military, which parallels other countries (e.g. Cape Canaveral/Vandenberg and Baikonur/Plesetsk). The first one is 50 km from Semnan, the provincial capital, some 226 km east of Tehran. Originally, it was a cement pad and blockhouses, but an impressive full-up vehicle assembly building was later constructed and the site was renamed Imam Khomenei Launch Centre (IKLC). The second is the further east: a more basic pad-and-blockhouses military site, 40 km from the similarly populated city of Shahrud. Rockets from both sites fly south southeast to the Arabian sea.

As for the rockets themselves, Iran’s original civil rocket, Safir, was Wasserfall/Scud-based, using unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide. It was a small launcher, typical of some of the more recent commercial companies worldwide: 22 m tall, 1.5 m in diameter and able to lift 60 kg to 450 km. Safir was used to launch Omid, Fajr, Rasad and Navid satellites, while a scaled-down version was used for the Kavoshgar suborbital missions.

The Omid satellite made Iran a space-faring nation.

The Omid satellite made Iran a space-faring nation.

Last year (2024) saw the introduction of its successor, Simorgh, 27 m tall, 2.5 m in diameter, and capable of reaching a 600 km orbit with heavier payloads. This launched not only the Fakhr satellite, but more importantly, a dummy Orbital Transfer Unit (OTU) that will later be used to send satellites to geostationary orbit.

For the military programme, Iran developed an indigenous solid propellant rocket, Qased, for the Nour missions. This was followed by the Qaim launcher, which can send 80 kg to a 750 km orbit, and Zuljanah, able to lift 200 kg to 500 km. As may be expected for a new spacefaring nation, Iran has had its share of failures, with reports of failed launches in 2008 (not confirmed), 2017, 2019 (two), 2020 and 2023. Sabotage was alleged in at least one case, not by Iran but by The New York Times.

As for tracking, the main Iranian base is Mahdasht, the original American Landsat site, renamed and modernised as Alborz Space Centre in 2020, with more antennas in Isfahan, Asad Abad and Boomehen. New antennas were installed at the old Caspian Sea listening site at Beshahr.

Perhaps the most difficult part of Iran’s space programme to measure is its institutional base

However, perhaps the most difficult part of Iran’s space programme to measure is its institutional base. Ever since the revolution, Iran has invested substantially in university and technical education, building its scientific and technical capacity, but western sanctions have intentionally had a significant economic impact, especially a brain drain of young technicians. Bloomberg’s most recent assessment, though, is that the space programme is able to grow despite the sanctions (see Einhorn & Golnar: ‘Iran’s space programme is growing stronger despite US sanctions’, Financial Post, 18 April 2025).

Rasad satellite ready for launch.

Rasad satellite ready for launch.

International context

Although Iranian human spaceflight is the stuff of rumour, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev reportedly made the first offer to fly an Iranian in 1990. Meanwhile, the Iranian Space Agency has announced intentions for a crewed mission, but a closer reading has always suggested that it would be suborbital rather than orbital; indeed, Mercury-sized spacecraft have been put on display.

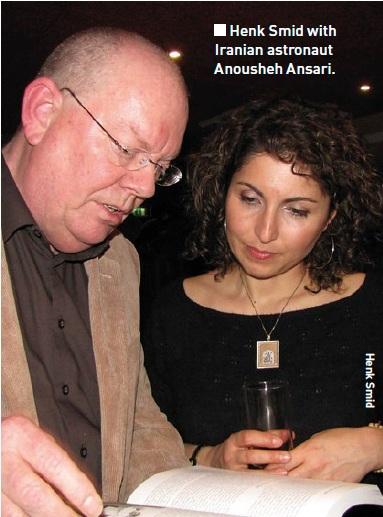

In 2013, President Ahmadinejad won headlines for volunteering for such a mission, but by then, Iran already had its first astronaut: Anousheh Ansari, a successful telecoms businesswoman who flew as an American tourist on a Russian spaceship, Soyuz TMA-09, in 2006. Her mission was followed with great enthusiasm in Iran at both official and popular level.

Rasad satellite.

Rasad satellite.

Although portrayed in western media in sinister terms, Iran’s liaison with Russia and China has ‘pragmatic’ written all over it and there has always been some distance between them. Russia and China can offer a full-spectrum experience, access to satellite makers and heavier launchers. Russia is a regular attender at the Kish, Persian Gulf Air Show, where it promotes its services and possible contracts, and a new cooperation agreement was signed earlier this year.

Iran has joined – indeed was a founder member of - the Asia Pacific Space Cooperation Organization (APSCO) and hosted its 11th annual summit. Iran has also participated in APSCO’s practical programmes for data-sharing, optical satellite observation and small satellite design, hosting several APSCO events and giving it access to its other member countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Mongolia, Peru, Thailand and Turkey. This has slowly but surely built up Iran’s capacity and human resources. Iran also belongs to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS+ (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and subsequent newcomers) which promote space cooperation for the global south and its allies.

As for future developments, Iran began a 10-year plan in 2024, the chief objective of which is a domestic geostationary communications satellite, for which the OTU was a preliminary test. This will require a new rocket, the Soroush, with a cryogenic engine called Bahman already in design. Iran has already started constructing a new 14,000 hectares launch site at Chabahar on the southeast coast for its launches to sun-synchronous and geostationary orbits from 2031, so it will probably be launched from there.

In the meantime, Russia will launch the first geostationary communications satellite for Iran, Eqvator, in 2026. Iran has an unfilled slot at 34°E, dating from the Shah’s time, and plans a network of 20 internet communications satellites, the Martyr Qassem Soleimani constellation, named after the IRGC Major General assassinated on President Trump’s orders.

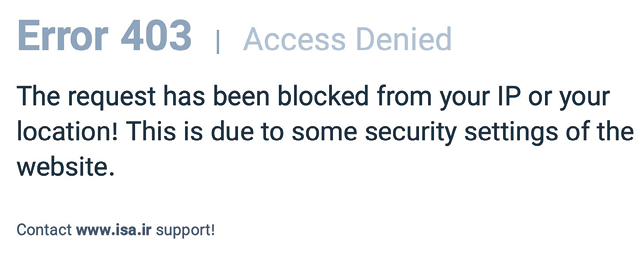

Sanctions: Iran Space Agency is blocked.

Sanctions: Iran Space Agency is blocked.

Politics and access

Although Iranian human spaceflight is the stuff of rumour, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev reportedly made the first offer to fly an Iranian in 1990

Few space programmes worldwide work within such explicitly political parameters as Iran, and here is where the country’s leadership has been important. The space programme did not progress until the presidency of Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) and the first launch took place during the time of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-13), the latter being the most visible, seen with the space programme on many occasions, attending a launch and even volunteering to be launched.

The programme retreated during the period of his successor, Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021), who responded to western concerns about dual use and tried to make an opening. As a gesture, the space programme was slowed and there were no successful launches from 2015 to 2020. Like Khatami before him, he was poorly rewarded, as President Trump renewed sanctions against Iran in 2017. Rouhani’s successor, Ebrahim Raisi (2021-24) resumed the pace and signed a ten-year plan. The current president, Masoud Pezeshkian, has been publicly supportive. The programme has broad support, and the three political pillars of the revolution - civil, religious and military - are often seen together at displays and events.

Russian stamp showing Iranian astronomer Al Buruni.

Russian stamp showing Iranian astronomer Al Buruni.

Iran’s space programme has developed despite a traumatic historical backdrop, including foreign invasions and occupation from 1804 to 1946, the American coup in 1953 and the revolution in 1979. Axis-of-evil sanctions remain an intentional force for economic and social destabilisation and retardation - indeed, Iran calls its society a ‘resistance economy’. It is no surprise that Iran has sought and obtained support from the two other full-spectrum space players, Russia and China, along with involvement in APSCO and now BRICS+ to slowly and patiently build its capacity.

Iran’s space budget is low, in the case of the Iran Space Agency only about €5 million a year with an overall civil total of €11 million or so. Nevertheless, it has achieved a space programme capable, since 2009, of launching small communications and observation satellites, civil and military, along with an infrastructure of institutions, two launch sites, ground stations and a new spaceport under construction.

Simorgh launcher.

Simorgh launcher.

Although Iran’s space programme is considered inaccessible and secretive, this is hardly Iran’s fault: the west’s cyberwarriors block access to the Iranian Space Agency. However, alternative sources of information include the Tehran Times and the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), both of which cover the space programme. Iran does not feel a compelling need to promote its space programme to the politically hostile west and its anglosphere, which, regardless of what it does, will give it a hard time. And although there are abundant English-language sources (e.g. Iran Daily, Mehr News Agency), western commentators rarely quote them.

Few westerners follow Iran’s space programme, still less learn Farsi or follow Iranian publications, scientific or technical papers. Iran has put on many displays of its space programme - obligingly for us in English - and attended the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Cape Town, when welcomed by fellow BRICS member South Africa in 2011. The best commentaries on Iran’s space programme used to be in Russian, in Novosti Kosmonavtiki. Space commentator Henk Smid [see box] visited Iran’s space programme twice, but few people have followed in his footsteps.

Few westerners follow Iran’s space programme, still less learn Farsi or follow Iranian publications

There is still a lot that we don’t know, but we have always to remember the wise CIA dictum that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence”. We lack in-house histories, technical details (especially engines), organigrams, mission results and presentations of future missions. ISA has participated at only one IAC, while statements at COPUOS are rare (Omid was an exception). Although we know the main actors (ARI, ISA, IGRC), we do not know how the decision-making process works, or the personalities involved.

Other Middle Eastern countries have space programmes, most impressively the United Arab Emirates with its Hope mission to Mars, but Iran’s is the most broad-based and programmatic. Like China, Iran considers itself a great scientific, astronomical civilisation and there is domestic pride in its progress. So, as far as Iran is concerned, it is definitely a case of ‘watch this space’.

About the author

Brian Harvey is a space writer and broadcaster based in Dublin, Ireland. He’s author of Japan in Space - Past, Present and Future (Praxis/Springer 2023), China in Space - the Great Leap (2nd edition) (Praxis/Springer, 2019), European-Russian Cooperation in Space - from de Gaulle to ExoMars (Praxis/Springer, 2021) and, with Gurbir Singh, The Atlas of Space Rocket Launch Sites (DOM, Berlin, 2022). Forthcoming: Space alliances - global leaders, friends and enemies (Praxis/Springer, 2028).